Workforce Planning

Last Updated: Sep. 8, 2020

Team Leads

- Luci Leykum, MD, MBA (University of Texas at Austin Dell Medical School)

- Marisha Burden, MD (University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus)

- Angela Keniston, MSPH (University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus)

Authors

- Gopi Astik, MD (Northwestern Medicine)

- Shaker Eid, MD, MBA (Johns Hopkins Medicine)

- Shradha Kulkarni, MD (University of California, San Francisco School of Medicine)

- Anne Linker, MD (Mount Sinai Hospital)

- Matthew Sakumoto, MD (University of California, San Francisco School of Medicine)

Workforce Planning Group Publications

Keniston A, Sakumoto M, Astik GJ, et al. Adaptability on Shifting Ground: a Rapid Qualitative Assessment of Multi-institutional Inpatient Surge Planning and Workforce Deployment During the COVID-19 Pandemic. J Gen Intern Med. 2022 Mar 22: 1-9.

Linker AS, Kulkarni SA, Astik GJ, et al; on behalf of the HOMERuN COVID-19 Collaborative Working Group. Bracing for the wave: a multi-institutional survey analysis of inpatient workforce adaptations in the first phase of COVID-19. J Gen Intern Med. 2021;36(11):3456-3461. DOI: 10.1007/s11606-021-06697-6

Keniston A, Sakumoto M, Astik G, et al. Sign of the times: Part 1: Hospitalists are indispensable in healthcare system COVID-19 responses. SGIM Forum. November 2021.

Topic Area

In late December 2019, COVID-19 began its global spread impacting hospitals and health systems across the globe. Hospital disaster planning has more typically focused on overcrowded emergency departments and decompressing emergency rooms, however in the case of COVID-19, hospitals faced a variety of new challenges.1-3 Health systems faced shortages in providers for patients on the wards and in the intensive care units, and also faced shortages in equipment and medications.4,5 Patients with COVID-19, at least early in the pandemic, seemed to have an average length of stay that was increased often with prolonged hospital stays in particular for patients requiring intensive care unit–level services, though this depends on the population studied.6 Communities were not equipped to have patients with a highly infectious disease transfer out to subacute nursing facilities or long-term acute care facilities, which caused further back logs in hospitals. With critical personal protective equipment on short supply7,8, institutions quickly had to modify current practices, which resulted in rapid innovations in staffing models and daily operations.5

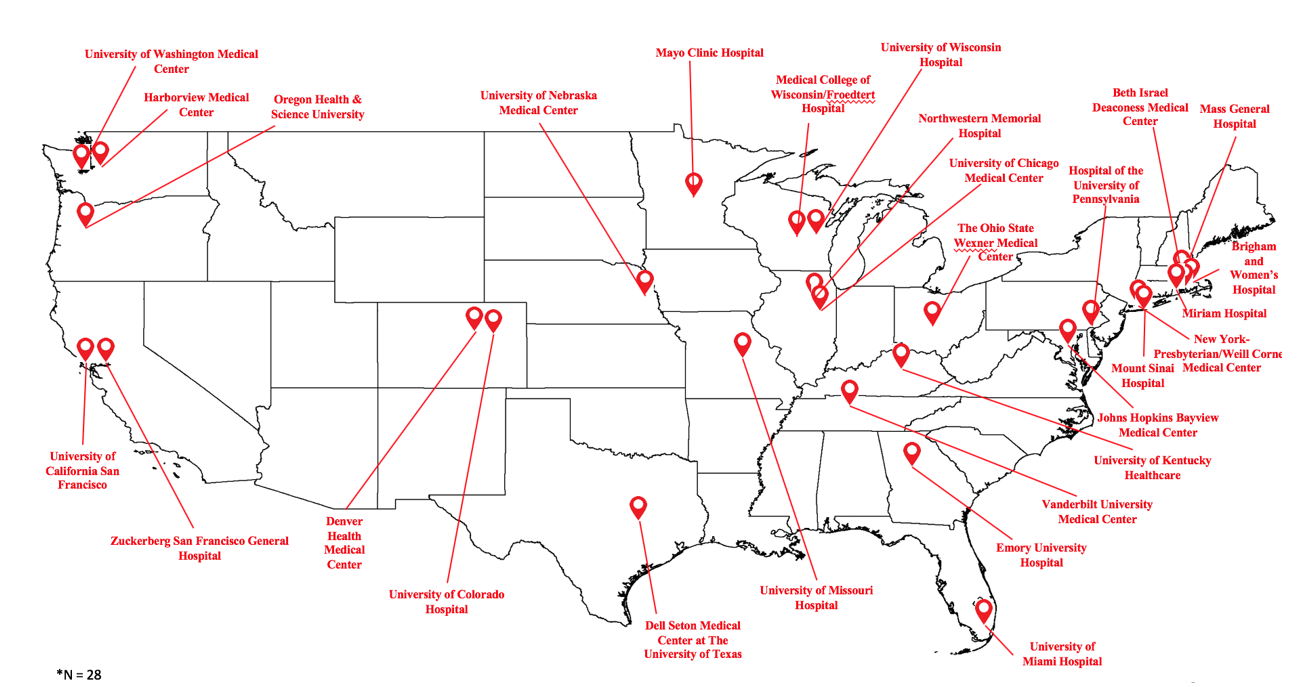

We conducted artifact review from approximately 10 health systems from across the United States. Based on those findings, we conducted a survey that was sent to 36 hospitals/hospital systems from May 18 to May 21, 2020. Twenty-nine sites responded to the survey (81% survey response). Themes that the survey covered came from our initial document review and broad experience from approximately 6 institutions who had experienced a surge. We further enhanced insights from our survey during HOMERuN Collaborative calls and will be carrying out more detailed site interviews.

Professional Society Guidance

- Chest has previously published a consensus statement for care of the critically ill and injured during pandemics and disasters.9

- Persoff and colleagues have published a framework for the role of hospital medicine in emergency preparedness10

- Our work highlights many of these principles in action and offers additional insights into practical approaches to managing the pandemic.

- Wiersinga WJ, Rhodes A, Cheng AC, Peacock SJ, Prescott HC. Pathophysiology, Transmission, Diagnosis, and Treatment of Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19): A Review. JAMA. 2020.

- Nicola M, Alsafi Z, Sohrabi C, et al. The socio-economic implications of the coronavirus pandemic (COVID-19): A review. Int J Surg. 2020;78:185-193.

- Ziv S. Coronavirus Pandemic Will Cost U.S. Economy $8 Trillion. Forbes. Accessed August 25, 2020.

- Bowden K, Burnham EL, Keniston A, et al. Harnessing the Power of Hospitalists in Operational Disaster Planning: COVID-19. J Gen Intern Med. 2020.

- Auerbach A, O’Leary KJ, Greysen SR, et al. Hospital Ward Adaptation During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A National Survey of Academic Medical Centers. J Hosp Med. 2020;15(8):483-488.

- Rees EM, Nightingale ES, Jafari Y, et al. COVID-19 length of hospital stay: a systematic review and data synthesis. BMC Med. 2020;18(1):270.

- George MP, Maier LA, Kasperbauer S, Eddy J, Mayer AS, Magin CM. How to Leverage Collaborations Between the BME Community and Local Hospitals to Address Critical Personal Protective Equipment Shortages During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Ann Biomed Eng. 2020;48(9):2281-2284.

- He S, Ojo A, Beckman AL, et al. The Story of #GetMePPE and GetUsPPE.org to Mobilize Health Care Response to COVID-19 : Rapidly Deploying Digital Tools for Better Health Care. J Med Internet Res. 2020;22(7):e20469.

- Einav S, Hick JL, Hanfling D, et al. Surge capacity logistics: care of the critically ill and injured during pandemics and disasters: CHEST consensus statement. Chest. 2014;146(4 Suppl):e17S-43S.

- Persoff J, Ornoff D, Little C. The Role of Hospital Medicine in Emergency Preparedness: A Framework for Hospitalist Leadership in Disaster Preparedness, Response, and Recovery. J Hosp Med. 2018;13(10):713-718.